What is utf-8 and why is it important for global digital communication?

“UTF-8” stands for “8-Bit UCS Transformation Format” and represents the most widespread character encoding on the World Wide Web. The international Unicode standard captures all language characters and text elements (virtually) of all world languages for data processing. UTF-8 plays a crucial role in the Unicode character set.

- Intuitive website builder with AI assistance

- Create captivating images and texts in seconds

- Domain, SSL and email included

The development of UTF-8 coding

UTF-8 is a character encoding. It assigns every existing Unicode character a specific bit sequence, which can also be read as a binary number. UTF-8 works by assigning a unique binary number to every character—letters, numbers, and symbols—from an ever-expanding range of languages. International organizations focused on setting internet standards, such as the W3C and the Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF), are actively promoting UTF-8 as the universal standard for character encoding. In fact, as early as 2009, the majority of websites had already adopted UTF-8. According to a W3Techs report from April 2025, 98.6% of all websites now use this encoding format.

Problems faced before UTF-8 was introduced

Different regions with related languages and writing systems developed their own coding standards because they had different needs. In English-speaking countries, for instance, the ASCII encoding was sufficient, as it allowed 128 characters to be represented as computer-readable strings.

Languages that use Asian scripts or the Cyrillic alphabet, however, require a much larger set of unique characters. Even German umlauts—such as the letter ä—are not included in the ASCII character set. On top of that, different encoding systems could assign the same binary values to entirely different characters. As a result, a Russian document opened on an American computer might appear not in Cyrillic, but in Latin letters mapped by the local encoding—producing unreadable text. This kind of mismatch seriously disrupted international communication.

Creation of UTF-8

To solve this problem, Joseph D. Becker developed the universal character set Unicode for Xerox between 1988 and 1991. From 1992, the IT industry consortium X/Open was also in search of a system to replace ASCII and expand the character repertoire. The coding was still meant to remain compatible with ASCII.

This requirement was not met by the first coding named UCS-2, as it simply transferred character numbers into 16-bit values. UTF-1 also failed because Unicode assignments partially collided with existing ASCII character assignments. A server set to ASCII thus sometimes output incorrect characters. This was a significant issue since most English-speaking computers operated this way at the time.

The next attempt was the File System Safe UCS Transformation Format (FSS-UTF) by Dave Prosser, which eliminated overlap with ASCII characters. In August of the same year, the draft circulated among experts. At Bell Labs, known for numerous Nobel laureates, Unix co-founders Ken Thompson and Rob Pike were working on the Plan 9 operating system. They adopted Prosser’s idea, developed a self-synchronizing coding (each character indicates how many bits it needs), and established rules for the assignment of letters that could be represented differently in the code (example: “ä” as its own character or “a+¨”). They successfully used the coding for their operating system and presented it to the authorities. Thus, FSS-UTF, now known as “UTF-8,” was essentially completed.

UTF-8 in the Unicode character set is a standard for all languages

The UTF-8 coding is a transformation format within the Unicode standard. The international standardization ISO 10646 largely defines Unicode, there known as the “Universal Coded Character Set.” The Unicode developers set certain parameters for practical application. The standard aims to ensure the internationally uniform and compatible coding of characters and text elements.

When Unicode was introduced in 1991, it defined 24 modern writing systems and currency symbols for data processing. In the Unicode standard published in 2024, there were 168. There are various Unicode Transformation Formats, or “UTF,” which reproduce the 1,114,112 possible codepoints. Three formats have prevailed: UTF-8, UTF-16, and UTF-32. Other encodings like UTF-7 or SCSU also have their advantages but have not been established. Unicode is divided into 17 levels, each containing 65,536 characters. Each level consists of 16 columns and rows. The zeroth level, the “Basic Multilingual Plane,” covers most of the writing systems currently used worldwide, along with punctuation, control characters, and symbols. Six additional levels are currently in use:

- Supplementary Multilingual Plane (Level 1): historical writing systems, rarely used characters

- Supplementary Ideographic Plane (Level 2): rare CJK characters (“Chinese, Japanese, Korean”)

- Tertiary Ideographic Plane (Level 3): more CJK characters have been encoded here since Unicode Version 15.1.

- Supplementary Special-Purpose Plane (Level 14): individual control characters

- Supplementary Private Use Area – A (Level 15): private use

- Supplementary Private Use Area – B (Level 16): private use

The UTF encodings provide access to all Unicode characters. The specific properties are recommended for certain areas of application.

UTF-32 and UTF-16 as alternatives

UTF-32 always operates with 32 bits, or 4 bytes. The simple structure increases the readability of the format. In languages that primarily use the Latin alphabet and thus only the first 128 characters, the encoding takes up much more storage space than necessary (4 instead of 1 byte).

UTF-16 established itself as a display format in operating systems like Apple macOS and Microsoft Windows. It is also used in many software development frameworks. It is one of the oldest UTFs still in use. Its structure is particularly suitable for memory-efficient encoding of non-Latin characters. Most characters can be represented in 2 bytes (16 bits), with the length doubling to 4 bytes only for rare characters.

UTF-8 if efficient and scalable

UTF-8 uses up to four sequences of 8 bits (one byte each), while its predecessor, ASCII, relies on a single 7-bit sequence. Both encodings represent the first 128 characters in exactly the same way, covering letters and symbols commonly used in English. As a result, characters from the English-speaking world can be stored using just one byte, making UTF-8 particularly efficient for texts in Latin-based languages. This efficient use of storage is one reason why operating systems like Unix and Linux use UTF-8 internally. However, UTF-8 plays its most important role in internet applications, especially when displaying text on websites or in emails.

Thanks to the self-synchronizing structure, readability is maintained despite the variable length per character. Without Unicode limitation, UTF-8 could theoretically allow 4,398,046,511,104 character mappings. Due to the 4-byte restriction in Unicode, it’s effectively 221, which is more than sufficient. Even the Unicode range still has empty planes for many more writing systems. The precise mapping prevents codepoint overlaps, which in the past limited communication.

While UTF-16 and UTF-32 also allow for precise mapping, UTF-8 utilizes storage space particularly efficiently for the Latin writing system and is designed so that different writing systems can exist alongside each other seamlessly and be covered. This enables their concurrent, meaningful display within a text field without compatibility issues.

The basics of UTF-8 coding and composition

The UTF-8 coding stands out not only for its backward compatibility with ASCII but also for a self-synchronizing structure, making it easier for developers to identify sources of error afterwards. For all ASCII characters, UTF uses only 1 byte. The total number of bit sequences can be recognized by the first digits of the binary number. Since ASCII code encompasses only 7 bits, the leading digit is the identifier 0. The 0 fills the storage to a full byte and signals the start of a chain without follow-up chains. The name “UTF-8” would be represented as a binary number with UTF-8 coding, for instance, as follows:

| Character | U | T | F | - | 8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UTF-8, binary | 01010101 | 01010100 | 01010100 | 00101101 | 00111000 |

| Unicode Point, hexadecimal | U+0055 | U+0054 | U+0046 | U+002D | U+0038 |

ASCII characters, like those used in the table, are assigned a single bit sequence by UTF-8 coding. All subsequent characters and symbols within Unicode have two to four 8-bit sequences. The first sequence is called the start byte, with additional sequences being continuation bytes. Start bytes with continuation bytes always begin with 11, while continuation bytes begin with 10. If you manually search for a specific point in the code, you can recognize the start of an encoded character by the markers 0 and 11. The first printable multi-byte character is the inverted exclamation mark:

| Character | ¡ |

|---|---|

| UTF-8, binary | 11000010 10100001 |

| Unicode Point, hexadecimal | U+00A1 |

Prefix coding prevents another character from being encoded within a byte sequence. If a byte stream starts in the middle of a document, the computer still displays readable characters correctly, as it doesn’t render incomplete ones. When searching for the beginning of a character, the 4-byte limitation means you only need to go back at most three byte sequences at any given point to find the start byte.

Another structuring element: The number of ones at the beginning of the start byte indicates the length of the byte sequence:

110xxxxxrepresents 2 bytes1110xxxxrepresents 3 bytes11110xxxrepresents 4 bytes

In Unicode, each byte value corresponds directly to a character number, which enables a logical, lexical order. However, this sequence includes some gaps. The range U+007F to U+009F is reserved for non-visible control characters rather than printable ones. In this section, the UTF-8 standard doesn’t assign any readable symbols—only command functions or control codes.

As mentioned, UTF-8 coding can theoretically link up to eight byte sequences. However, Unicode prescribes a maximum length of 4 bytes. This results in byte sequences of 5 bytes or more being invalid by default. Moreover, this restriction reflects the aim to create code that is as compact—using minimal storage space—as possible, and as structured as possible. A fundamental rule when using UTF-8 is to always use the shortest possible encoding.

However, for some characters, there are multiple equivalent encodings. For example, the letter ä is encoded using 2 bytes: 11000011 10100100. Theoretically, it’s possible to combine the code points for the letter “a” (01100001) and the diaeresis mark “ ” (11001100 10001000) to represent “ä”: 01100001 11001100 10001000. This uses the so-called Unicode Normalization Form NFD, where characters are canonically decomposed. Both encodings shown lead to the exact same result (namely “ä”) and are therefore canonically equivalent*.

Normalizations are used to unify different Unicode representations of the same character. Canonical equivalence is important because it means that two sequences of characters can be encoded differently but have the same meaning and appearance. Compatible equivalence, on the other hand, also allows sequences that differ in format or style but are substantively the same. Unicode normalization forms (e.g., NFC, NFD, NFKC, NFKD) use these concepts to standardize texts. This ensures that comparisons, sorting, and searches work consistently and reliably.

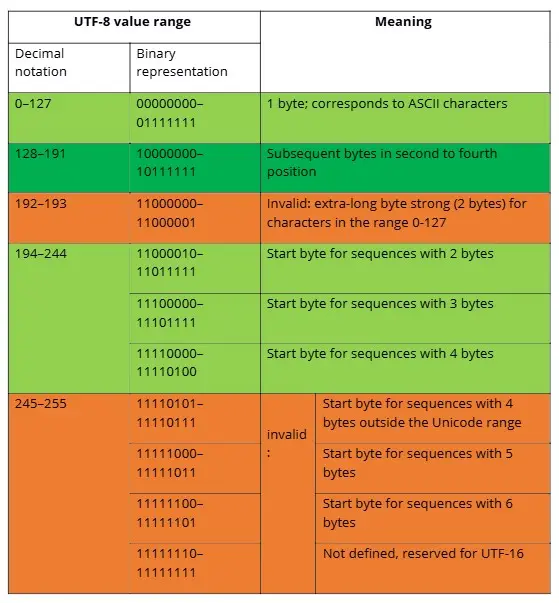

Some Unicode value ranges were not defined for UTF-8 because they are reserved for UTF-16 surrogates. The overview shows which bytes in UTF-8 under Unicode are considered valid according to the Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF) (green marked areas are valid bytes, orange marked are invalid).

Conversion from Unicode Hexadecimal to UTF-8 binary

Computers read only binary numbers, while humans use a decimal system. An interface between these forms is the hexadecimal system. It helps to compactly represent long chains of bits. It uses the digits 0 through 9 and the letters A through F and operates on the base of the number 16. As the fourth power of 2, the hexadecimal system is better suited than the decimal system for representing eight-digit byte ranges.

A hexadecimal digit represents a quartet (“nibble”) within the octet. A byte with eight binary digits can therefore be represented with just two hexadecimal digits. Unicode uses the hexadecimal system to describe the position of a character within its own system. From this, the binary number and finally the UTF-8 codepoint can be calculated.

First, the binary number must be converted from the hexadecimal number. Then you fit the codepoints into the structure of the UTF-8 coding. To simplify the structuring, use the following overview, which shows how many codepoints fit into a byte chain and what structure can be expected in which Unicode value range.

| Size in Bytes | Free Bits for Determination | First Unicode Codepoint | Last Unicode Codepoint | Start Byte / Byte 1 | Follow Byte 2 | Follow Byte 3 | Follow Byte 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 7 | U+0000 | U+007F | 0xxxxxxx | |||

| 2 | 11 | U+0080 | U+07FF | 110xxxxx | 10xxxxxx | ||

| 3 | 16 | U+0800 | U+FFFF | 1110xxxx | 10xxxxxx | 10xxxxxx | |

| 4 | 21 | U+10000 | U+10FFFF | 11110xxx | 10xxxxxx | 10xxxxxx | 10xxxxxx |

Within a given code range, you can predict the number of bytes used because the lexical order is consistent in both the Unicode codepoints and the corresponding UTF-8 binary values. For the range U+0800 to U+FFFF, UTF-8 uses 3 bytes. This range provides 16 bits to represent the codepoint of each symbol. The binary number is integrated into the UTF-8 encoding from right to left, with any unused bits on the left filled with zeros.

Calculation example:

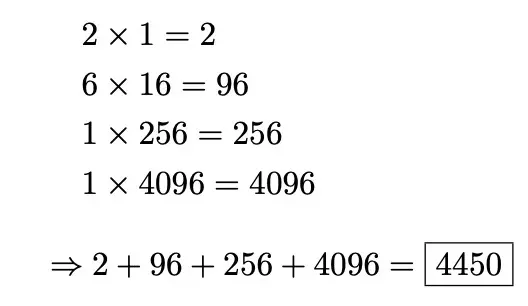

The characterᅢ (Hangul Junseong, Ä) is located at position U+1162 in Unicode. To calculate the binary number, first convert the hexadecimal number into a decimal number. Each digit in the number corresponds to the correlating power of 16. The rightmost digit has the lowest value with 160 = 1. Starting from the right, multiply the digit’s numeric value by the power’s value. Then, add up the results.

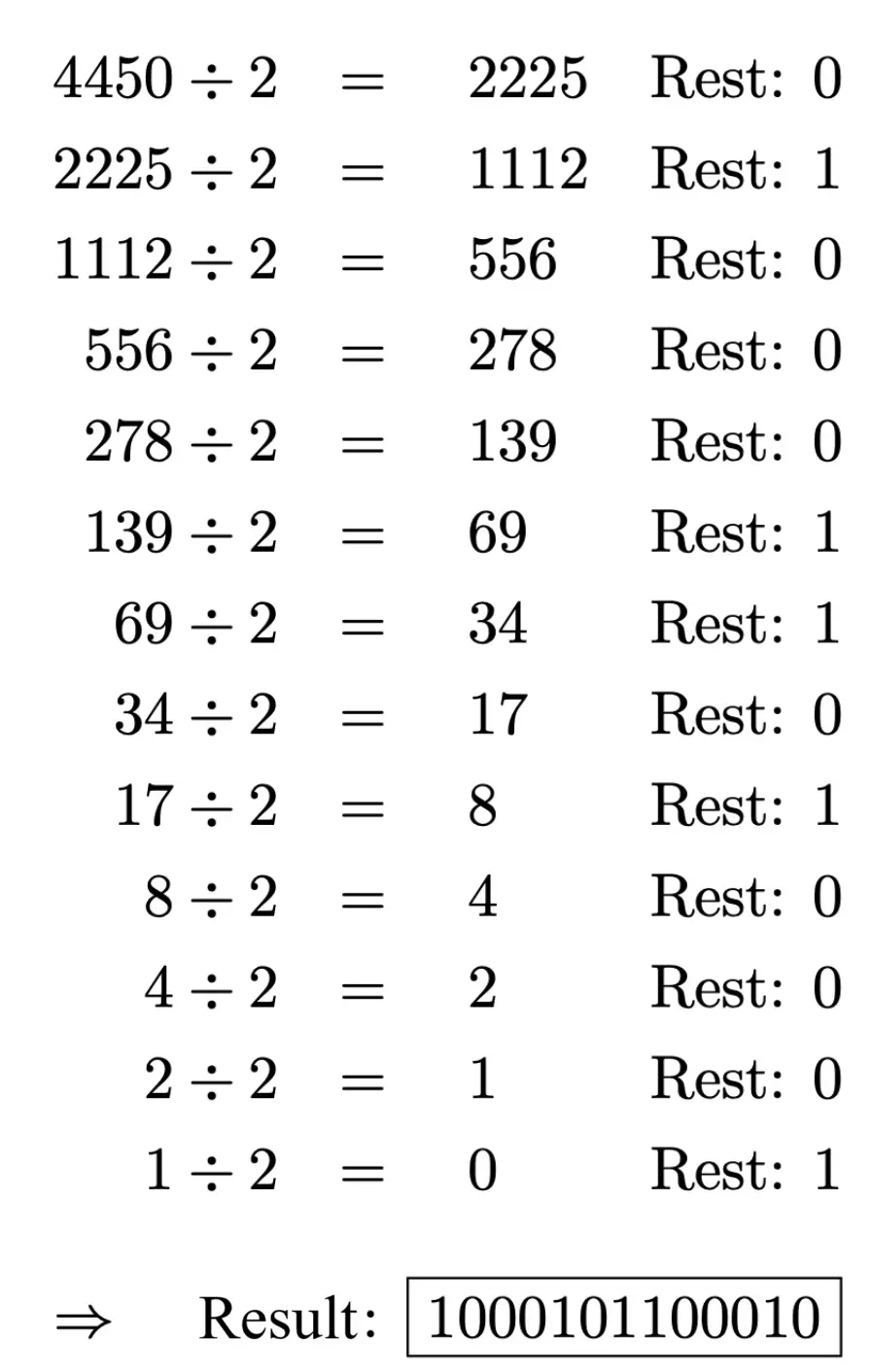

4450 is the calculated decimal number. Now, convert this into a binary number. To do this, repeatedly divide the number by 2 until the result is 0. The remainder, written from right to left, is the binary number.

The UTF-8 code prescribes 3 bytes for the codepoint U+1162 because the codepoint is between U+0800 and U+FFFF. Therefore, the start byte begins with 1110. The two subsequent bytes each start with 10. Fill in the binary number in the free bits, which do not dictate the structure, from right to left. Complete remaining bit positions in the start byte with 0 until the octet is full. The UTF-8 coding then looks like this:

11100001 10000101 10100010 (the inserted codepoint is bold)

| Character | Unicode Codepoint, hexadecimal | Decimal number | Binary number | UTF-8 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ᅢ | U+1162 | Decimal number | 4450 | 1000101100010 | 111000011000010110100010 |

UTF-8 in the Editor

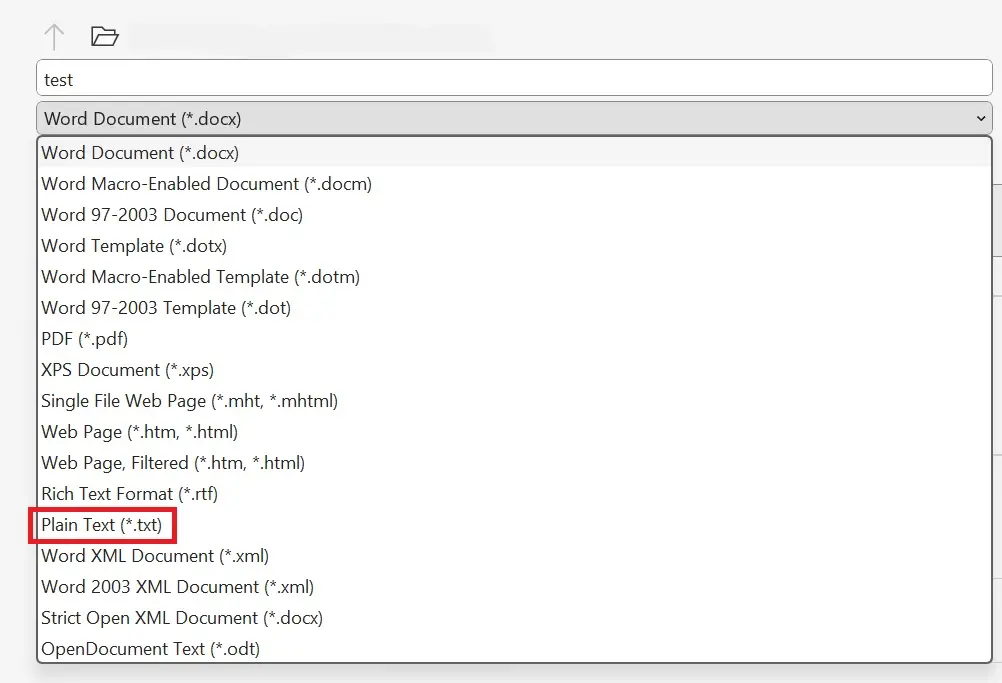

UTF-8 is the most widespread standard on the internet, but simple text editors do not necessarily save texts in this format by default. Microsoft Notepad, for instance, uses a default encoding referred to as “ANSI” (which is actually the ASCII-based encoding Windows-1252). If you want to convert a text file from Microsoft Word to UTF-8 (for example, to represent various writing systems), proceed as follows: Go to “Save As” and select “Plain Text” in the File Type option.

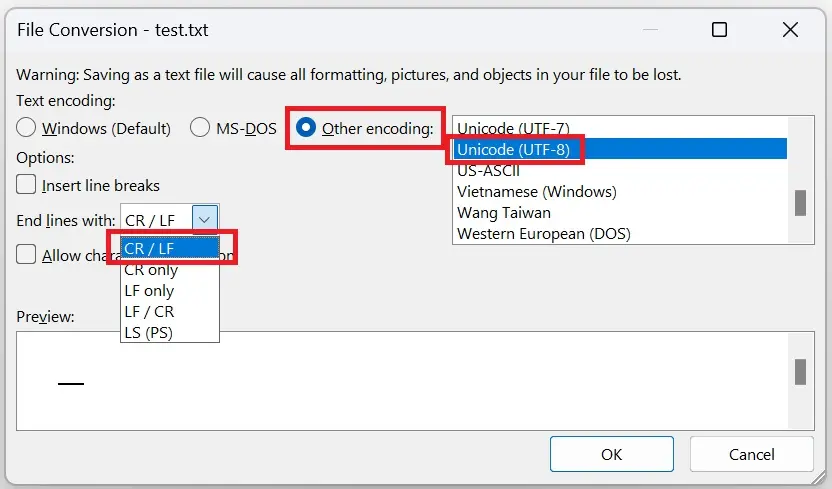

The pop-up window “File Conversion” will open. Under “Text Encoding”, select “Other encoding” and from the list, choose “Unicode (UTF-8)”. In the drop-down menu “End lines with”, choose “Carriage Return/Line Feed” or “CR/LF”. This is how you easily convert a file to the Unicode character set with UTF-8.

Opening an unmarked text file, where you don’t know beforehand which encoding was applied, can lead to issues during editing. In Unicode, the Byte Order Mark (BOM) is used for such situations. This invisible character indicates whether the document is in Big-Endian or Little-Endian format. If a program decodes a UTF-16 Little-Endian file using UTF-16 Big-Endian, the text will be output incorrectly.

Documents based on the UTF-8 character set do not have this problem, as the byte order is always read as a Big-Endian byte sequence. In this case, the BOM merely serves as an indication that the document is UTF-8 encoded.

Characters represented with more than one byte can have the most significant byte at the front (left) or the back (right) in some encodings (UTF-16 and UTF-32). If the most significant byte (MSB) is at the front, the encoding is labeled “Big-Endian.” If the MSB is at the back, “Little-Endian” is added.

You place the BOM before a data stream or at the start of a file. This marker takes precedence over all other directives, even over the HTTP Header. The BOM acts as a sort of signature for Unicode encodings and has the code point U+FEFF. Depending on the encoding used, the BOM appears differently in its encoded form.

| Encoding Format | BOM, Code point: U+FEFF (hex.) |

|---|---|

| UTF-8 | EF BB BF |

| UTF-16 Big-Endian | FE FF |

| UTF-16 Little-Endian | FF FE |

| UTF-32 Big-Endian | 00 00 FE FF |

| UTF-32 Little-Endian | FF FE 00 00 |

Do not use the Byte Order Mark if the protocol explicitly prohibits it or if your data is already assigned a specific type. Some programs, according to the protocol, expect ASCII characters. Since UTF-8 is backward compatible with ASCII coding and its byte order is fixed, you don’t need a BOM. In fact, Unicode recommends not using the BOM with UTF-8. However, since they can appear in older code and cause problems, it’s important to identify any existing BOM as such.

- Professional templates

- Intuitive customizable design

- Free domain, SSL, and email address