What is an accessible website and why does it matter?

Accessible websites ensure that users with a wide range of disabilities and needs can use websites without limitations and without assistance from others. The purpose of an accessible website is therefore to prevent the exclusion of certain groups online—for example, people with physical or intellectual disabilities.

- Get online faster with AI tools

- Fast-track growth with AI marketing

- Save time, maximize results

What is an accessible website?

In order to make an accessible website, this involves designing web content in a way that allows all users to access and understand it. This includes people who rely on assistive technologies such as screen readers, keyboard navigation, magnification tools, or captioning. As part of creating an inclusive online experience, accessible websites are essential for businesses, organizations, and public institutions. Accessible web design can also improve search engine optimization by enhancing usability and information structure.

Barriers are obstacles that make it difficult — or in some cases impossible — for users to access and interact with website content. While awareness of accessibility in physical spaces has grown significantly, barriers on the web still arise frequently and often unintentionally. These can be caused by technical decisions, visual design choices, or poorly structured content. Research and practical examples show that interactive components, such as logins or security features, can present major challenges. Certain CAPTCHAs using distorted characters or visual-only puzzles can significantly limit access for people with visual impairments and conflict with current expectations for accessible websites.

Web accessibility standards for accessible websites

The key international standard for accessible websites is the WCAG—specifically WCAG 2.2 (Web Content Accessibility Guidelines). These W3C guidelines define the latest requirements and best practices that make websites accessible to all users.

WCAG 2.2 emphasizes improved usability, clearer keyboard and focus navigation, and simplified interactions on mobile devices. These updates reflect evolving user behavior and address barriers that earlier versions did not fully cover.

Some of the most important WCAG 2.2 success criteria include:

- Visible keyboard focus: Interactive elements must be clearly visible when navigated using a keyboard.

- Minimum size of controls: Clickable and touchable areas must be large enough to avoid accidental activation.

- Alternatives to drag movements: Interactions must not rely exclusively on drag-and-drop.

- Avoiding redundant input: Users should not need to re-enter the same information multiple times.

- Accessible authentication: Login processes must not depend on cognitive tasks such as puzzle-based CAPTCHAs.

WCAG 2.2 is the main benchmark for modern website development and forms the technical foundation for accessibility requirements in the United States.

In the United States, website accessibility requirements are primarily defined through the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) and the Rehabilitation Act (Section 508). These frameworks establish clear guidelines for businesses, public institutions, and federally funded organizations and rely on WCAG standards to determine whether a website meets accessibility requirements.

| WCAG POUR Principle | Measure | Primary target group |

|---|---|---|

| Perceivable | Provide content that works without relying solely on visual or auditory cues (e.g., alt text, strong color contrast, captions, avoiding background audio) | People with visual impairments, color blindness, Deaf users, older adults |

| Operable | Support keyboard navigation and assistive technologies, provide large click/touch targets, clear page structures, intuitive menus | Screen reader users, people with motor disabilities, mobile users, older adults |

| Understandable | Use clear language, explain technical terms, avoid abbreviations, logical content grouping | People with cognitive disabilities, older users, inexperienced users |

| Robust | Use semantic HTML, ARIA labels, ensure compatibility with assistive technologies, accessible forms with clear field associations | All assistive technology users, screen magnifier users |

Perceivable

Many websites include flashing ads, comment sections are filled with small-font text, and sometimes background music even plays to reinforce the page’s mood or theme. Depending on the type and severity of a disability, some visitors to your website may not perceive these elements fully—or at all.

Blind people, for example, navigate the internet without visual cues. Instead, a screen reader reads the website aloud. The device passes the readable data to the assistive technologies being used. A refreshable Braille display, for instance, can convert text into Braille. This allows the person to perceive your website through touch. A text-to-speech tool plays the content in audio format. With this technology, users rely on hearing to process website content. In the example just mentioned, however, the background music then becomes a distraction.

People with a less severe visual impairment—including many older adults—can take in your website’s content with their eyes, but they rely on a highly magnified display. People with color vision deficiency, on the other hand, may not notice warnings that are conveyed only through color. Deaf people, in turn, cannot access the information in audio-only files and much of the content in video files.

Understandable

Very young users, older adults, or people with cognitive disabilities may struggle to understand texts filled with technical language, unexplained abbreviations, or complex sentences. If a website separates related content or uses inconsistent terminology, users may find it difficult to grasp the intended meaning.

Operable

As mobile browsing continues to grow, it becomes especially frustrating when links are too small or too close together to tap accurately. Websites that aren’t optimized for smartphones—where tightly packed, tiny link text is common—can be particularly difficult for older adults or anyone with limited hand steadiness.

However, many tools have now been developed for people with physical disabilities that make it easier to use computers. For this purpose, some tools track eye movements, while other technologies are operated via the keyboard. In principle, a website designed for web accessibility should be built so it can be interpreted by such assistive technologies. If your website can’t be navigated with them, potential customers who rely on them have no chance to use your full range of offerings.

When users are asked to fill out a form—for example, to sign up for a newsletter—errors are not uncommon. The password is too short, or the date of birth doesn’t fit the specified parameters. Therefore, provide clear guidance on how to fix errors. Interacting with a website also includes navigation. People who use devices with small displays or work with high screen magnification need navigation paths tailored to that and rely on a clear, well-structured website.

Comment sections allow users to provide feedback. They can use them to share their opinion about a product or content, or to communicate with other people. When typing on a monitor, people with visual impairments often use a screen magnifier. This makes elements appear much larger and increases the distance between the reading column and the input field. Therefore, place the elements visually close together to make it easier for users to engage with each other.

Robust

Websites must be compatible with assistive technologies through proper code structure. Semantic HTML (like <main>, <nav>, <section>) helps screen readers understand page organization. Proper form labels connect input fields to their descriptions using for attributes. ARIA landmarks provide shortcuts for screen reader navigation. Without these, even well-designed content becomes unusable for assistive technology users.

- Intuitive website builder with AI assistance

- Create captivating images and texts in seconds

- Domain, SSL and email included

What are the benefits of accessible web design?

Removing accessibility barriers improves the usability of your website and strengthens your visibility in search engines. Many accessibility practices overlap with best practices in user experience and SEO, meaning that improvements made for accessibility often benefit all visitors.

An accessible website helps:

- users on mobile devices,

- people with physical or cognitive disabilities,

- older adults, and

- visitors who may be unfamiliar with web navigation.

By presenting information clearly and structuring your website logically, you increase both readability and the amount of time users spend on your pages. While accessibility does require additional work and testing, the benefits are extensive. Accessible websites provide a better experience for everyone.

How to make a website accessible? Tips and examples

If you want to build an accessible website, you should pay close attention to how you structure information as well as various visual components of the site.

Step 1: Ensure a clear information structure

Give your website a logical, easy-to-follow structure and use straightforward, user-friendly language. This makes your content more accessible and also improves your Google ranking, since search engines evaluate readability and clarity.

To support strong SEO and maintain an organized site architecture, keep the following in mind:

| Element in website architecture | Rationale |

|---|---|

| Clear naming of URLs and content | Every page should make its topic immediately clear, improving both navigation and comprehension. |

| Easy-to-follow structure | Users can always see where they are on the site and how content relates to other sections. |

| Flat hierarchies | Content should be accessible within just a few clicks, making navigation faster and more efficient. |

| Separation of layout and content | Using CSS ensures that content remains structured and accessible for assistive technologies such as screen readers. |

| Meaningful, organized categories | Subpages should have a logical semantic relationship to the parent page. |

| Web-optimized presentation of content | Content should display correctly across all devices and browsers. |

| User-friendly language | Clear phrasing and explained terminology support comprehension for all audiences. |

| Key website sections always accessible | Pages such as Contact, search, or the homepage should be reachable from any subpage with one click. |

| Consistent navigation elements | A uniform navigation structure supports better orientation. |

| Sitemap and FAQ for large websites | A sitemap and FAQ help users locate information quickly. |

| Scalable fonts and responsive layout | Text and layout should work well for users with magnification or on smaller screens. |

| Usability with mouse and keyboard | Websites should be fully operable without a mouse and compatible with assistive input methods. |

| Alternative text for images | Alt text supports screen reader interpretation and improves accessibility and SEO. |

Step 2: Use visual cues

Scalable fonts and color adjustments help people with low vision or color blindness read website content more easily. Ensure that text has sufficient contrast from the background and that interactive elements such as buttons or links stand out clearly.

To help users who navigate with a keyboard or screen reader, highlight interactive elements through:

- visible focus indicators,

- hover effects,

- active link styles.

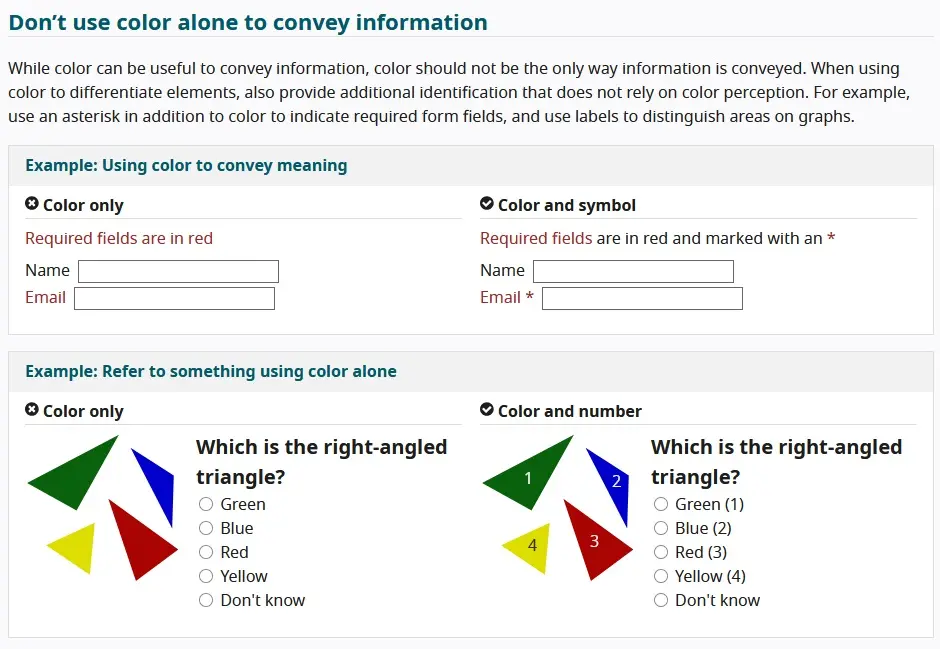

Do not rely solely on color to convey meaning — supplement color coding with symbols, numbers, or asterisks.

People who experience epileptic seizures are at risk if a website contains graphics or videos that flash more than three times per second. Researchers have also found that sharply defined, high-contrast grid patterns can trigger seizures in people with photosensitive epilepsy as well.

| Problem | Accessible measure | Benefits most |

|---|---|---|

| Low color contrast | High-contrast color schemes | People with low vision |

| Flashing content | Avoid or limit it | People with epilepsy |

| Small font sizes | Scalable fonts | Older adults |

Step 3: Present information in multiple formats

Ensuring that your website is and remains accessible should be part of your daily workflow. Whether you’re optimizing for search engines, publishing PR content, or adding new product pages, regularly uploaded content should be structured in a way that is usable for all visitors.

A fundamental part of website accessibility — with SEO benefits — is including alt text for images. Because crawlers and screen readers cannot interpret images, alt text provides meaningful descriptions for:

- blind users,

- people with low vision,

- users on slow internet connections.

| Media type | Accessible alternative | Target audience |

|---|---|---|

| Images | Alt text | Screen reader users |

| Videos | Captions, audio description | Deaf users, people with visual impairments |

| Audio | Transcripts | Deaf users |

Transcripts and captions

Creating transcripts and captions on a continuous and timely basis is a more extensive task. These tools allow you to make audio content accessible to people who are Deaf or hard of hearing. A transcript, which converts spoken words as well as sounds and background noises into text, should be placed as close as possible to the associated audio content — for example, via a button that links directly to the document.

Captions make it significantly easier for people who are Deaf or hard of hearing to understand web videos. They also benefit users who prefer not to play audio (for instance, because they don’t want to disturb others). People with cognitive disabilities or conditions such as ADHD often process video content more effectively when they can mute background sounds using a video player setting — similar to users with hearing impairments.

Audio description

People with visual acuity below 30 percent are considered visually impaired, and those with visual acuity below two percent are considered blind. They perceive visual information only partially or not at all. To ensure that these individuals can understand your video content, you should include an additional audio track. This track provides explanations of visual elements such as landscapes, people, and short descriptions of actions taking place on screen. Place these explanations in the speech and audio pauses of the original recording so that the audio tracks do not overlap.

Easy-to-read language

Easy language expresses content in a very simple way. It helps people with cognitive disabilities understand complex information more easily. Easy language avoids elements such as the subjunctive, synonyms, and negations. Sentences are short and contain only one idea at a time. People with cognitive disabilities have the same right to information as everyone else. For this reason, daily newspapers increasingly provide versions of their articles in easy language on their online platforms as a good example of accessible websites. Public institutions are also using easy language more frequently in their informational texts.

A less strict form is what’s known as easy-to-read language, which roughly corresponds to language level A2 or B1.

Step 4: Make the website compatible

Assistive technologies such as screen readers make web accessibility possible for many users. These tools process websites linearly from left to right and top to bottom, which is why layout and content must be separated cleanly. Otherwise, page elements may be interpreted incorrectly.

To help users navigate efficiently, follow these core rules.

Skip navigation links and other shortcuts

Screen readers pass text information to text-to-speech software and refreshable braille displays. To do this, they read the page from top to bottom—this also includes repeating elements such as the navigation bar, icons, or links to subpages. To prevent the reader from unnecessarily repeating this information on every page, you should implement skip navigation links (short: skip links).

Users who navigate using only a keyboard, possibly with a mouth stick, also struggle a lot if they have to tab through numerous elements. These people benefit from a skip link at the top of the page that is as visible as possible:

<a href="#content">Skip navigation</a>

<main id="content">

<h1>Main heading</h1>

<p>First paragraph</p>

</main>There are skip links that are invisible in the layout, but the screen reader relays the alternative text message “Skip navigation” to the user when the code looks like this:

<a href="#content"><img src="empty.gif" height="15" border="0" alt="Skip navigation" width="5"></a>It’s important that skip links appear as early as possible in the code. Place the anchor target at the beginning of the main content:

<div id="content"></div>Use skip links sparingly, as too many of them can cancel out their positive effect and force users to click through an excessive number of elements. A more elegant solution is to use ARIA landmarks and ensure a well-structured document. It is also advisable to use HTML5 elements.

Another helpful feature is a table of contents at the beginning of the document, which allows users to jump to specific sections via in-page links. Modern screen readers read the corresponding headings aloud. By using meaningful, well-structured headings, you improve readability for both search engines and assistive technologies.

Data tables instead of layout tables

For accessible websites under W3C web accessibility guidelines, ideally use only data tables. Screen readers have fewer issues with this format and can present the information meaningfully after conversion. Layout tables, on the other hand, give a page visual structure but make it harder for screen readers to convey the content clearly.

Define layout tables using only simple elements: TABLE, TR, and TD (table, row, and cell, respectively). Use structural elements to make the relationships between cells logical; then the screen reader will read the layout table like a data table. You do the opposite if you remove certain table elements from the accessibility tree.

For your web accessibility efforts, use the code role="none" as shown in the example. This applies to the table and its child elements. If you nest tables within tables, you must define both elements with it.

<table role="none">

<tr>

<td>

<table role="none">

<tr>

<td>

Example text <abbr title="for example">e.g.</abbr> about ARIA

</td>

</tr>

</table>

</td>

</tr>

</table>Checklist for accessible websites

Once you’ve finished building your website, reviewing our web accessibility checklist can help you make sure you’ve considered the key factors.

✓ Information structure is well organized and easy to follow

✓ Use of clear, accessible language

✓ Alt text for images

✓ Video and audio transcripts

✓ Color highlighting for important content

✓ High contrast

✓ Screen reader support

It may not surprise you that the W3C website is a prime example of a web-accessible online presence. It includes the core elements required by the standards:

- Plain language

- Clearly structured HTML

- Indicator for the currently selected elements

- Color contrast

- Clear and easy-to-follow structure

Free tools for creating accessible websites

There are a number of tools that can help you build an accessible website. Below are some of the most well-known options:

- WAVE Web Accessibility Evaluation Tool (WebAIM): Tool for testing website accessibility, fully aligned with ADA/Section 508.

- Accessibility Checker: This web app allows you to test your site for WCAG compliance free of charge.

- Siteimprove: Siteimprove’s Accessibility Checker offers a free website scan, with the results delivered by email.

Website accessibility improves the UX for everyone

Improving accessibility on your website enhances overall usability and significantly improves the user experience. This benefits:

- mobile users,

- people with physical or cognitive disabilities,

- older adults, and

- anyone who may be less comfortable navigating the web.

By structuring your website clearly and preparing content in an inclusive, easy-to-understand format, you support both accessibility and search engine optimization. Clear architecture, strong contrast, readable text, and assistive-technology compatibility all contribute to longer visit durations and higher satisfaction rates.

While ensuring accessibility requires additional work—such as thorough testing, clear content structure, alternative text, and thoughtfully designed interaction elements—the investment is well worth it. Accessible website design benefits all users, strengthens brand credibility, and helps you reach a wider audience, including those who rely on assistive technologies to navigate the web.